Earls Court, London’s former “Gay Central”

Giorgio Petti

London, as every metropolis, has always attracted gay and lesbian people. In the days before social media and the internet and even more in days when male homosexuality was still on the criminal books (lesbian relationships were never a crime in the UK, but male to male ones were so until 1967), there was an obvious need for the gay community to meet and socialise in places where its members could feel accepted and more or less openly display their sexuality. Often these venues, including bars and clubs cluster around an area, people move in the area as a result and a district acquires a distinct 'alternative' feel.

However London is a fluid metropolis and over the course of the years 'gay districts' have shifted around its territory. Looking at Soho or Vauxhall today one may be led to believe that these areas have long been London's 'gay central'. And yet, if one had walked around Soho in the late 70s or even the early 80s it would have been hard to find anything but seedy strip joints and decrepit bars fleecing the occasional straight tourist.

Similarly there are areas that once were the centre of everything gay, but now are a very distant memories of those heady times. Earls Court is one of them. For many years this has been (and to some extent still is) a place notorious for its transient population, lured by its (then) cheap housing, often in large Victorian mansion blocks. In fact in the 70s this area was nicknamed 'Kangaroo Valley', because of its large number of Australian residents on their UK temporary visas. Today, with house prices tens of times higher and parts of the area boasting prices amongst the dearest in the city, backpackers have moved on, though the area is still home to many cheap hotels and hostels.

Just stepping out of Earls Court underground, outside of which stands the only remaining TARDIS police telephone box made so famous in Dr Who. Once dodged the inevitable crowd of tourists taking pictures, turning left and up a short 2 minutes walk up the road at number 180-182 used to be the Copacabana, later Club 180. Today it's a Wagamama restaurant and a separate bar, but starting in the late 70s and up to the mid 90s here was London's first public nightclub aimed at a gay clientele. The Copacabana was at the forefront of the then emerging clone scene and featured a bar upstairs called Harpos and the Banana Max. One wonders if the diners at Wagamama are at all aware of the dance shenanigans that once happened there.

A bit up the road and passed the junction with the Cromwell Road, on the left is Logan Place. Here at no 1 was the residence of Freddie Mercury who also died here in 1991.

Back to the station and continuing along the Earls Court Road we reach the Old Brompton Road. On the left at 60 Colherne Court lived Diana Princess Of Wales before his engagement to Charles in 1981. She owned a flat here, which had been donated to her by her parents and had two lodgers at that time.

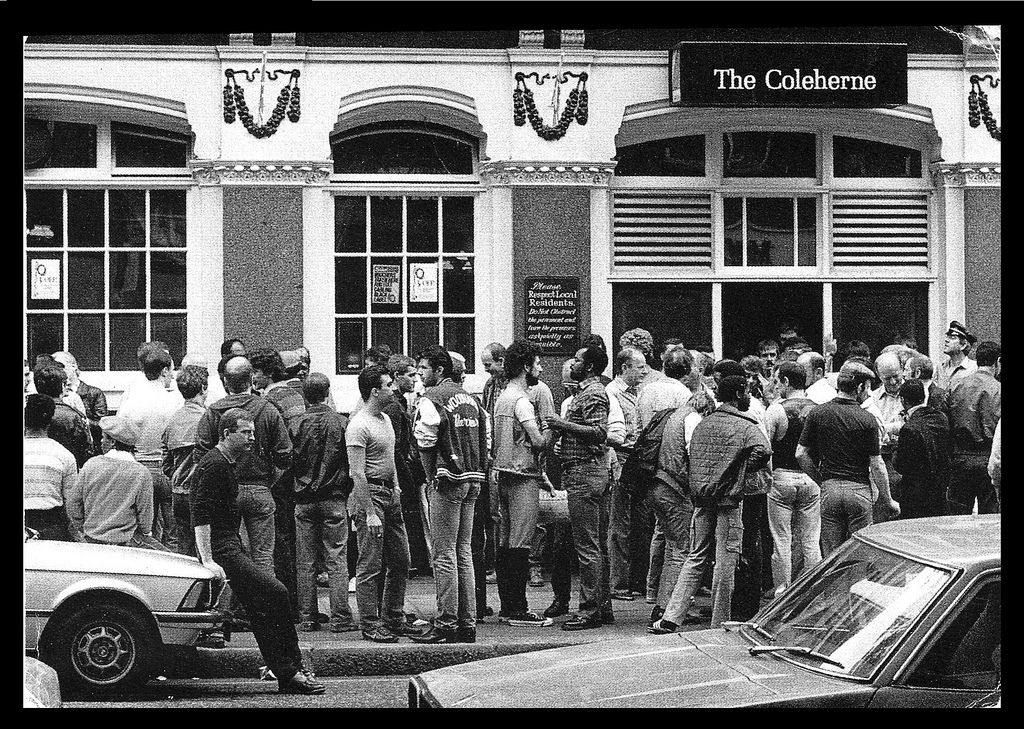

The segment between here and the Warwick Road used to be the epicentre of gay life up to the late 80s. First of all the old Colherne Pub, which is now a straight ordinary gastro-pub called The Penbroke. In its original name the pub stood there since the 1880s and always attracted a Bohemian clientele, in fact it has been reported that already in the late 1930s there were drag entertainers performing at weekends. Gays informally started attending in the 50s but it was in the 70s that the pub turned itself into a leather bar, with blackened windows and acquired worldwide fame. So much that the Colherne is also featured in Armistead Maupin's book 'Babycakes', part of the Tales of The City series. Famous regulars were Freddie Mercury, Rudolph Nureyev and Kenny Everett. The venue also had a number of less salubrious regulars, as it was also the stalking ground of three serial killers, including Colin Ireland, known as 'The Gay Slayer', who murdered five people and died in HM Wakefield Prison in 2012, aged 57.

Next to the Colherne was a small underground dance club, known as The Catacombs. Empty for many years, it was recently converted into a luxury residential apartment and sold for £2.5m.

A few doors down Old Brompton Road, on the opposite side, stands a branch of Clone Zone, one of the few remainders of the time when this was a thriving gay centre. Clone Zone started as a small retail stall in the nightclub that used to be at the corner of Old Brompton and Warwick Road. Originally named The Lord Ranelagh, it was famous as 'Bromptons' in the 80s and early 90s.

In September 1964 a young, non-gay, male band, The Downtowners, persuaded many of the local cross-dressers to come into the Lord Ranelagh and perform in a show called 'Queen of the Month'. The shows proved very successful and every Saturday night the pub was packed to capacity. However the also attracted the attention of homophobic tabloids and in May 1965 The News of The World published an an article entitled 'This show must not go on.'The massive publicity ensured that on the Sunday night the pub was so packed that every table and chair had to be removed. Crowds spilled out on to the pavement onto Old Brompton Road. The police closed the show. Many well-known celebrities were among the clientele and the Lord Ranelagh is thus considered to have played a role in the history of gay liberation in the UK.

On the opposite side from the Lord Ranelagh and down a few hundred meters along Old Brompton Road is Brompton Cemetery. This is one of the 'magnificent seven' London burial grounds and features in its centre a beautiful Victorian columnade, which is built over Catacombs - a particularly popular form of burial in those times. The cemetery, with its long grass in places is still a very popular cruising ground, possibly one of the most eeriest and peculiar around.

Earls Court's popularity in the gay community surged at a time where talks of LGBT equality were in their infancy, though many older members of our community would swear that the scene back then was far more interesting and alternative than today's. It is certain that the weight of the HIV/AIDS epidemic that swept through the community in the early 80s and the institutional homophobia of Thatcher's Section 28 changed the scene, including the one that was at that time thriving around Earls Court. The passage from the heady disco days of the late 70s to the more sombre times of the 80s was punctuated by so many sad losses in our community. But it was the progressive gentrification of the area that caused the community to move on. Higher prices in Chelsea and Kensington meant the area started to be seen as a natural extension of much richer districts. Then by the late 80s and early 90s Westminster Council was eager to redevelop Soho and cracked down on the seedy straight clubs, thus more or less deliberately attracting the gay community to move in the void.

Earls Court's gay scene was by then history.